Seattle built a 1.2 mile two-way protected bike lane in just 4 months and in Pittsburgh it took 4 months to announce, build and install their first three protected bike lanes. Seattle and Pittsburgh are cities with leadership (and bike advocates!) that have a strong commitment to bike infrastructure, evident by the quality and speed at which they're building.

While local conditions will always vary, seeing cities quickly building quality bike infrastructure demonstrates what is possible with committed, forward thinking leadership.

What do we love about how bike infrastructure is getting built in Seattle?

It's being built quickly. The 2nd Ave bike lane "Originally on schedule for construction in 2016, Murray gave SDOT directions in May to make a protected bike lane happen before Pronto Cycle Share launches in late summer. Four months is a very fast timeline for a project of this scale, but SDOT delivered. Now the city has a jump start on creating a safer and more comfortable bike network in the city center." — Seattle Bike Blog

Volunteers and signs are telling people about changes. In addition to signage, like in the photos below, the local advocacy group mobilized volunteers to be stationed along the new lane at its opening to answer questions.

The city continues to iterate on the design once they see how people are using it. After a new bike lane opened, the city made several changes to improve problem intersections, including improved “no turn on red” signage and changing green balls to straight arrows.

They're building bike infrastructure in coordination with public transit infrastructure.

For example, the two-way protected bike lanes on Broadway were created as part of the $134 million First Hill streetcar expansion.

What do we love about how bike infrastructure is getting built in Pittsburgh?

It's being built quickly. It took Pittsburgh 4 months to announce, build and install their first three protected bike lanes. That's really fast!

Mayor Peduto has a bold, unwavering commitment to building protected bike infrastructure. He said, "It isn't the way it was in 1970. Not everyone's dream is to have their own car and be able to use it to get to work. [...] When you talk about the bike infrastructure and the investment and capital dollars to build it out, you're really not talking about bike lanes. What you're talking about is a multimodal approach to building out your infrastructure."

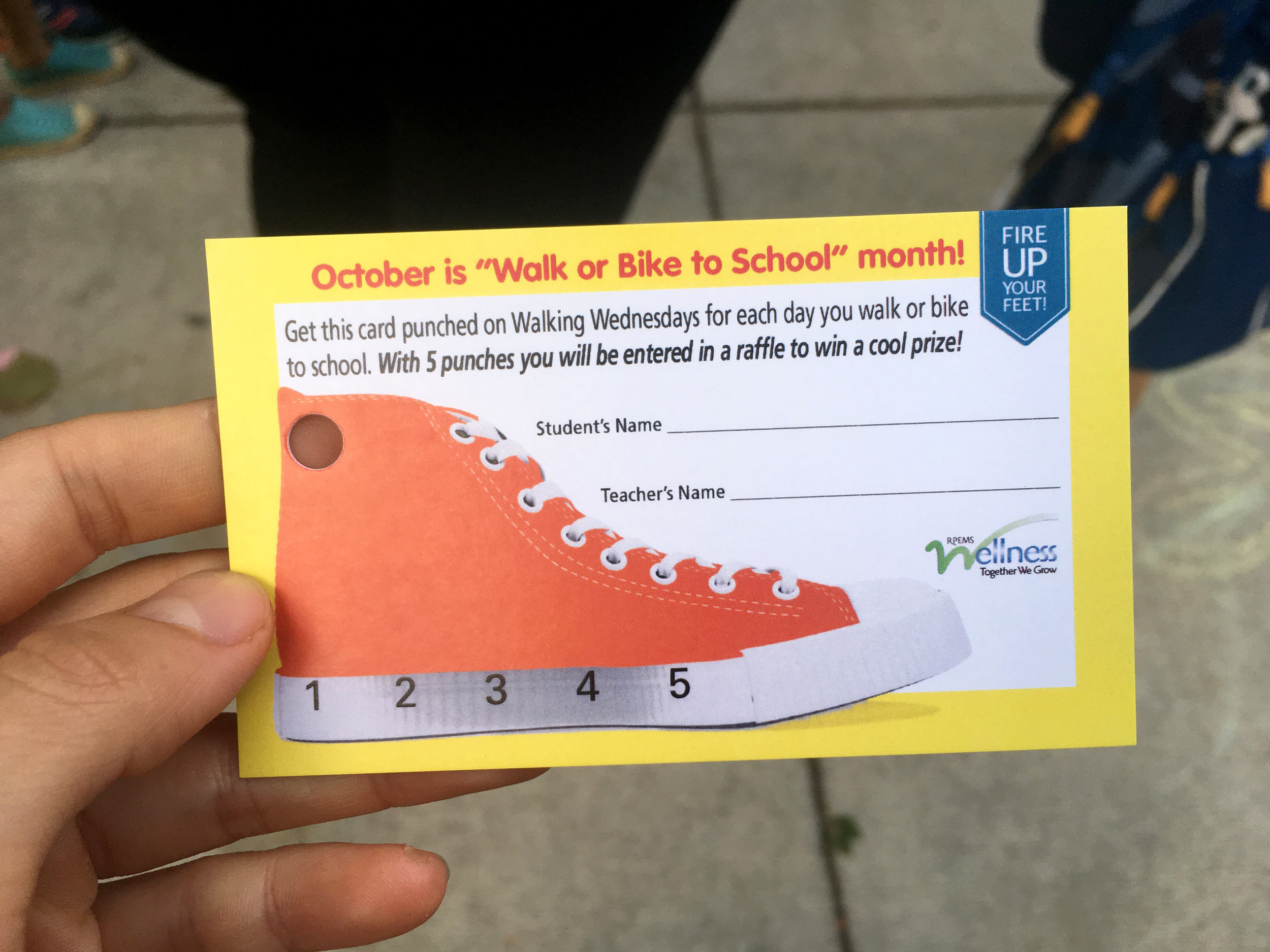

While community involvement in these projects has been questioned, we believe bike infrastructure projects are strongest with both committed and fearless city leaders and sustained engagement with communities. And here in Baltimore, we're definitely committed to both, with a combination of efforts like #DirectDOT and our community engagement campaign for the Downtown Bike Network.

The city put their money where your mouth is by passing a particularly bike friendly city budget. This included significant funding for protected bike lanes, bike infrastructure in a diversity of neighborhoods, funding for bike racks, improved sidewalks, and more.

Mayor Peduto issued a Complete Streets Executive Order, which was unanimously adopted by Planning Commission, and affirmatively recommended for City Council to adopt. This ensures that a complete streets vision is carried through all city departments in the design, construction, and maintenance and use of the city's streets.

They're building bike lanes within a complicated landscape of hills, bridges, narrow and non-grid streets. Pittsburgh, not unlike Baltimore, is a city with characteristics that make bike infrastructure and biking itself difficult: tons of hills, bridges, windy roads, and a strong car culture. But the city is taking that as a challenge rather than a barrier.

According to Bike PGH, census numbers show that bike commuter rates doubled since Pittsburgh began vigorously installing bike lanes in 2007. Seattle and Pittsburgh demonstrate what is possible, and act as an illustration of what we can and should be asking for from Baltimore leadership.

→ Share your vision for a Baltimore that builds quality bike facilities on a reasonable timeline through our #DirectDOT campaign!